Image by Zoya Lymar. From personal archive.

We live in a wonderful time when you can keep track of history not just with the written word, but also through photographs and movies. All the while, people keeping the annals of time, seldom ever make it into the spotlight: for them telling stories about others takes precedence over seeking recognition themselves.

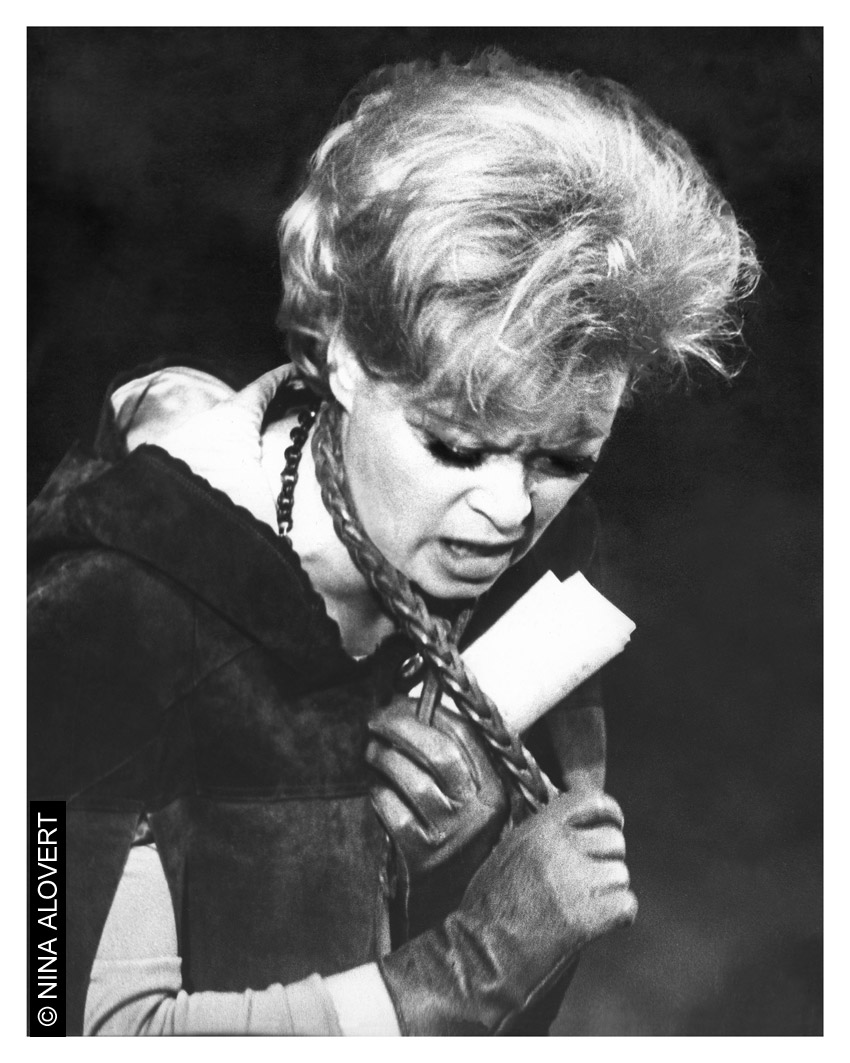

Nina Alovert is one of these “chronographers”. Her medium is photography and because of that we'll be able to honor those who we speak of, listen to, and watch — not only by telling the stories to our children, but actually showing them. The heroes of her photographs are safe, unaffected by time, they will live on. Unaffected by time, safe from aging and death, her subjects are immortalized in their relative youth.

Emmy award and Benois de la Danse award winner, photographer and ballet academic Nina Alovert is a collector — gathering the most influential people in arts of XX and XXI centuries. Sergey Dovlatov, Joseph Brodsky, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Vladimir Visotsky, Marina Vlady, Makhail Kozakov, Solomon Volkov, Natalia Makarova, Vladimir Voinovich, Nikolai Tsiskaridze, Diana Vishneva and many been numerously times captured through her lens.

One evening, in New York, we've sat down to talk about what it's like to live behind that lens.

Images courtesy of the artist

Sasha Korbut: Nina, in 1977 you left the Soviet Union for the U.S. Why did you decide to emigrate?

Nina Alovert: For a very primitive reason — I saw an opportunity to escape the Soviet regime. I did not want my children to grow up there and wanted a different world for myself. Besides, I was the adventurous type. I was 42 when we left — it's the prime of a woman's life, the height of energy, supported by sufficient life experiences. Kids were still very young — I didn't have to convince them of anything. My mother, on the other hand, needed some persuasion: by that time she was 72 years old and frightened to move at first, but eventually she got behind it. I understood that I'm jumping off a cliff, in a sense, whilst not knowing how and where I'll land. At the same time it wasn't that scary — we were emigrating as refugees, part of Tolstoy foundation, thus knowing in advance we will have support on the other side, basic food and shelter, and go from there.

SK: Now, decades later, do you think you made a right call — to leave?

Mikhail Baryshnikov

NA: Yes, I do. My life, and particularly my career — wouldn't have been fulfilling. For example, I would have never published a book about Baryshnikov, the one that started it all — in 1985 a publishing house in New York printed both my text and photographs. Around the same time, still barely speaking the language, I went to the offices of Dance Magazine and showed them my work. I couldn't take anything with me when I left the Soviet Union; some of my film negatives were acquired by Leningrad museum, rest was illegally smuggled by friends. Not everything, but most of the photographs survived. So, after printing them, I went straight to the publisher.

They were very welcoming, asked me a lot about the Russian ballet. Back then, with "Iron Curtain" still in place, Americans were particularly curious about what was happening in Soviet Union. I became friends with them, and we have worked together ever since. Simultaneously I went to the New Russian Word magazine, and claimed I can write about ballet, although at the time I had little of any experience — my courage making up for that. Everything seemed easy back then.

When we first met, the editor-in-chief told me: “We had a fire at the printer's yesterday, we suspect it's arson. If you do me a favour and take pictures of those burnt printing presses — you'll have a job for the rest of your life.” So I took some pictures. And, that way, began to write about ballet.

Sergei Dovlatov

SK: A fragment from a novel by Sergei Dovlatov comes to mind, it describes the lives of immigrants in America at that time: a publicist, well known in Russia, but who became an absolutely inglorious immigrant to the United States, came to Baryshnikov with a plea for help. Baryshnikov gave him $2000 and the priceless advice to requalify as a masseuse. Did you also have to go through something like that?

NA: Yes, I did, I was a hostess at a little restaurant in Greenwich Village, cleaned flats, and scrubbed toilets, and never thought of that and something degrading, because I did it to support myself and my kids and make time to do my work.

SK: During your recent visits the homeland, TV channel "Russia" invited you as a guest to the show «Soviet defectors or loop of solitude». The title of the show itself makes clear that its subjects are emigrants, and attitude to them is nowhere near friendly. Why did you accept the invitation?

“Everybody is trying to depict emigrants to the Russian people as some sort of poor and unhappy people.”

NA: I had no idea what the title of the show will be, let alone about what kind of points they were making. I was told that the show will be dedicated to the great Russian emigrants: Alexander Godunov, Rudolph Nureyev и Mikhail Baryshnikov. I was even wondering at that time, and ask them: why Godunov? He wasn't that great at all. I suggested Natalia Makarova to them — for she is really one of the greats. They have explained that they will be making a separate production about her.

Natalia Makarova Giselle 1968

SK: Later, after the show’s release, you wrote in a critical article: "Godunov was part of the program to be a single example of tragically failed path of the Russian artist in the West. But there is hardly anyone to blame for the Godunov's tragedy of alcohol and substance abuse."

I wanted to clarify: when you said the “single example” did you mean out of all artist-emigrants, or just those who were mentioned on the show.

NA: Only those who were mentioned. Of course many unknown artists have failed to succeed in the West, but we were specifically talking about people who were supposed to be destined to succeed.

SK: Why do you think they have raised the topic of defectors again?

NA: I don't know why, everybody is trying to depict emigrants to the Russian people as some sort of poor and unhappy people. You said it yourself the name of the show says «Loop of solitude». But who was in solitude over here? Was it Baryshnikov who had four children? Nureyev, surrounded by a crowd of friends and fans? Makarova, that had a beautiful family: husband (who had unfortunately passed away recently) and a child?

Of course there are those people, who are suffering, who shouldn't have left and are homesick. But there are others who were just startled and couldn't make something of themselves here, just like Godunov — he was in need of a guiding hand — a person who would've cared for him. He was just that kind of man.

Nikolay Tsiskaridze

“My opinion is that modernists lost the sense of drama, and just move to the sounds of music. There is not enough theater in contemporary ballet.”

SK: Let's talk about your photographs of dancers. In one of your interviews you said "I hear the dancer dancing on stage. I can write a monologue for the performance, if I'm on the same wave as him". How often does that happen to you?

NA: Quite often but I can't anticipate it. This feeling, of understanding the actor, is very much like love. Where does the love come from? I don't know. Just as well I look for the most beautiful part in the artist's performance and try to capture that.

Diana Vishneva

SK: Reading your critical articles about ballet I noticed that you pay special attention to the creativity of Diana Vishneva. Is she close to your heart?

NA: Yes, I think I can feel her on stage particularly well, I understand her, love her. I am touched by the depth and diversity of her talents, not just as a dancer but as an actor... She is my number one ballerina in the world, and the most interesting one right now.

SK: Would you put her on the same level as titans of the Russian ballet — Baryshnikov, Nureyev and Makarova?

NA: Yes, I would.

SK: Are you interested in contemporary ballet?

NA: Yes, I am very interested to see how ballet evolves and changes through time. Saying that, I can tell you that "modern", real modern had stopped for me on Martha Graham. I don't like as much everything that followed. My opinion is that modernists lost the sense of drama, and just move to the sounds of music. There is not enough theater in contemporary ballet.

SK: You have captured an incredible number of Soviet stars with your camera. Were they well-disposed towards being your subjects?

NA: I was photographing dancers mostly in performance, from the audience or backstage. So I never asked, and there wasn’t anyone to ask that sort of thing. In the States I took a lot of pictures of my compatriots, because I believed we needed to not miss that period in Russian history. Thus, because I was walking around with a camera — I had to take pictures of everyone I met. So all of it was documentary photography. And nobody raised any objections.

SK: Have you considered that your pictures became famous not just because of your eye and talent, but also because they depicted people who since then became historical figures?

NA: I haven’t thought about that. You know, I was rarely inquiring into my fame… And I was genuinely surprised to learn that I am known in Russia. I was taking photographs just because I loved theater. And I continue to do the work I love.